Often-repeated misconceptions and historical fallacies regarding airway beacons and concrete directional arrows

by David M. DuPree

1. MYTH: The airway beacons were dismantled when the U.S. entered WWII to prevent enemy forces from using them for navigation.

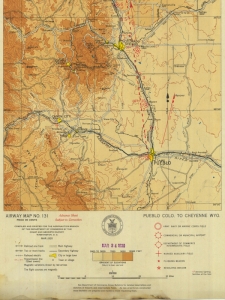

As America began preparing for war in the late 1930s, the number of airway beacons continued to increase, peaking at the end of 1941 and remaining relatively constant from year to year for the duration. From 1939 through 1941, 357 rotating airway beacons were added to the nation’s lighted airways. Amber Civil Airway No. 8, extending along the California coastal region from Los Angeles to San Francisco, was built during 1941 and continued operating through the war years. Aside from infrequent, localized and brief blackouts, the lighted airways – even the coastal routes – remained operational as a wartime necessity. During blackout exercises, airway beacons were specifically exempt. It wasn’t until the postwar period that the number of beacons returned to the 1937-1938 levels. Between 1940 and 1945, there were more airway beacons operating in the U.S. than at any other time in history.

2. MYTH: The airway beacon towers were scrapped during WWII because the steel was needed for the war effort.

The airway beacons were an essential part of the war effort. Many new beacons were added to the system beginning in the late 1930s (see above). WWII resulted in an immediate and massive increase in air traffic from coast to coast. This included unprecedented levels of military flight training, as well as the movement of personnel and materiel on a grand scale. The light beacons remained indispensible for night navigation throughout the war.

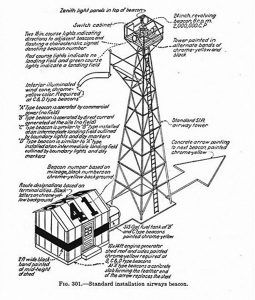

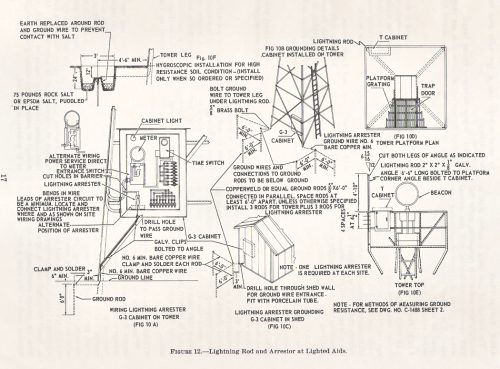

3. MYTH: The large directional arrows were the first navigation aids on the airways and the beacons were added later.

Rotating beacons were in use on the airways as early as 1923. Directional arrows were not introduced until late 1926 or early 1927. Concrete arrows were built only as daytime visual aids to supplement the rotating airway beacons and other site markings.

4. MYTH: Large directional arrows were built and used by the U. S. Air Mail Service.

I have found no evidence that the Post Office Department (U. S. Air Mail Service) ever built or utilized directional arrows on its airways (1918-1926). There is no known record or documented instance of an Air Mail Service pilot relying on large directional arrows for course information. The first concrete directional arrows were built after the Department of Commerce assumed responsibility for the development, construction and maintenance of the federal airways in late 1926. Though used by contract air mail operators, the arrows were not established by the U. S. Air Mail Service.

5. MYTH: Concrete directional arrows were located at all federal airway beacon sites.

Concrete directional arrows were included in construction specifications for airway beacon sites only from 1927 to 1932. However, even during that period not all beacon sites included concrete arrows. In fact, there were entire airways from that period that were not equipped with arrows. For instance, some coastal routes didn’t need large directional arrows for daytime navigation since they were already equipped with the ultimate visual marker – the coastline. As with most aspects of configuring and equipping airways and individual beacon sites, the airway engineers determined whether arrows were needed. In any case, you are unlikely to find a concrete arrow at an airway beacon site built after 1932. Fewer than half of all airway beacon sites included a concrete arrow.

6. MYTH: The concrete directional arrows were illuminated at night.

As originally envisioned by the Department of Commerce in 1927, the concrete arrows were to be illuminated by lights mounted overhead on the beacon towers. This was implemented at some sites during 1927, but it was soon determined to be impractical due to several factors. Among other things, the spotlighting was inadequate for making the arrows distinguishable at night, and at remote locations, the limited wattage provided by the on-site generators was increasingly needed for other things, including the newly introduced course lights. The arrows remained in the plans, but they became directional aids for day, visual conditions only.

7. MYTH: The airway beacons were in service for only a few years.

Airway beacons were operated continuously on the federal airways from 1923 until the mid-1960s, a period spanning more than four decades. The decommissioning of airway beacons was a gradual process that began in the 1950s. The final large-scale decommissioning occurred in the mid-1960s. The rotating beacons guided the early Air Mail’s open-cockpit biplanes, the classic planes of the Golden Age, the American air armada of WWII and the majestic postwar prop airliners. The big lights continued serving well into the jet age. A few beacons continued to operate into the 1970s and beyond. The State of Montana still operates several airway beacons, while a few more around the country have been maintained as hazard/landmark beacons. Upon retirement from airway service, hundreds of surplus beacons and towers went to work at airports, where they continued to serve as navigation aids. Refurbished and sometimes updated with high-tech lamps, some of these beacons (and towers) have been operating for more than 80 years!